Gabrielle Grace Hogan (she/her) is a lesbian poet and essayist who received her MFA from the New Writers Project at the University of Texas at Austin. Her work has been published by TriQuarterly, CutBank, Salt Hill, Missouri Review, and others. She has published two chapbooks, Soft Obliteration (Ghost City Press 2020), and Love Me With the Fierce Horse Of Your Heart (Ursus Americanus Press 2023). She is a Team Writer for Autostraddle. Find more information on her website, gabriellegracehogan.com.

Instagram: @gabriellegracehogan

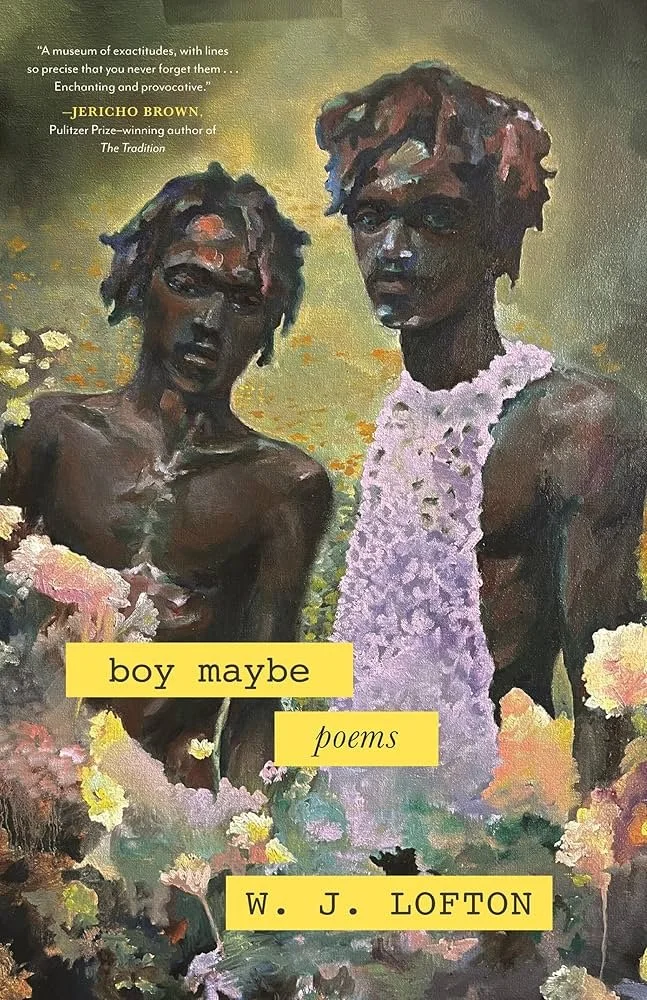

W. J. Lofton, born in Chicago and raised in Valley, Alabama, is a Black and queer Southern poet. He is the author of boy maybe (Beacon Press, 2025). A recipient of fellowships from Cave Canem and Emory University Arts and Social Justice Program, Lofton lives in Atlanta.

- Review of boy Maybe by W.J. Lofton -

By Gabrielle Grace Hogan

“we wanted to live. / we had reasons to be alive.” So says WJ Lofton in boy maybe, a decadent, dripping collection. The poems within these pages are like breaths in a chest as it rises and falls: a reminder that life is happening, that within us is its fierce capacity. As Lofton’s third collection, it’s clear the poet has found a steady stride in his storytelling, and a wealth in his images. The collection is described as being “about love and flirtation, sweet tea and hot sauce, God and family, life and death, police brutality and extrajudicial killings” by the publisher, Beacon Press; this quote emphasizes the polyhedral dimensions of these poems, in that they cannot be pinpointed to one aspect of queer or Black or southern identity. There is simply too much to contain.

From the get-go, Lofton admits to being unable to do it on his own — as in, his poems both acknowledge their place in a greater history of Black queer literature, and treasure it. From June Jordan to Langston Hughes, but also from Frank Ocean to Kendrick Lamar: there is no pretension about what can count as inspiration.

In “to know touch better,” the speaker proclaims “still we were faggots before & after they killed us,” touting an acidic and aspirational statement, that regardless of what a hateful society may do, who we are prevails. The personal as political as art is ever-present in this collection, combining the poem’s flowered lyric with the hot knife of state violence, and the slick heat of sexual tension. Touch is the god at the center of this collection’s religion: it can be provided as refuge from the violence of the world, and it can enact it. In “counting,” the speaker talks of his parents as “my life depends on their touching.” In “butcher shop,” the speaker recounts what he “touched trying to understand / Love,” referring to other bodies, and then later in the same poem remarks that “Bullets touched them the way men touch countries / When they believe in nothing,” comparing the impact of domestic and global violence. Like any tool, touch can be a weapon or a gift depending on the hand — a truth boy maybe expertly unveils.

In “half brutal,” “futures are being told.” This collection is one that imagines all possible futures, in all possible hands, all laid against the body of the reader, reading to hold.